The top five myths of Irish history that Irish People believe

#5 The Mother and Child Scheme

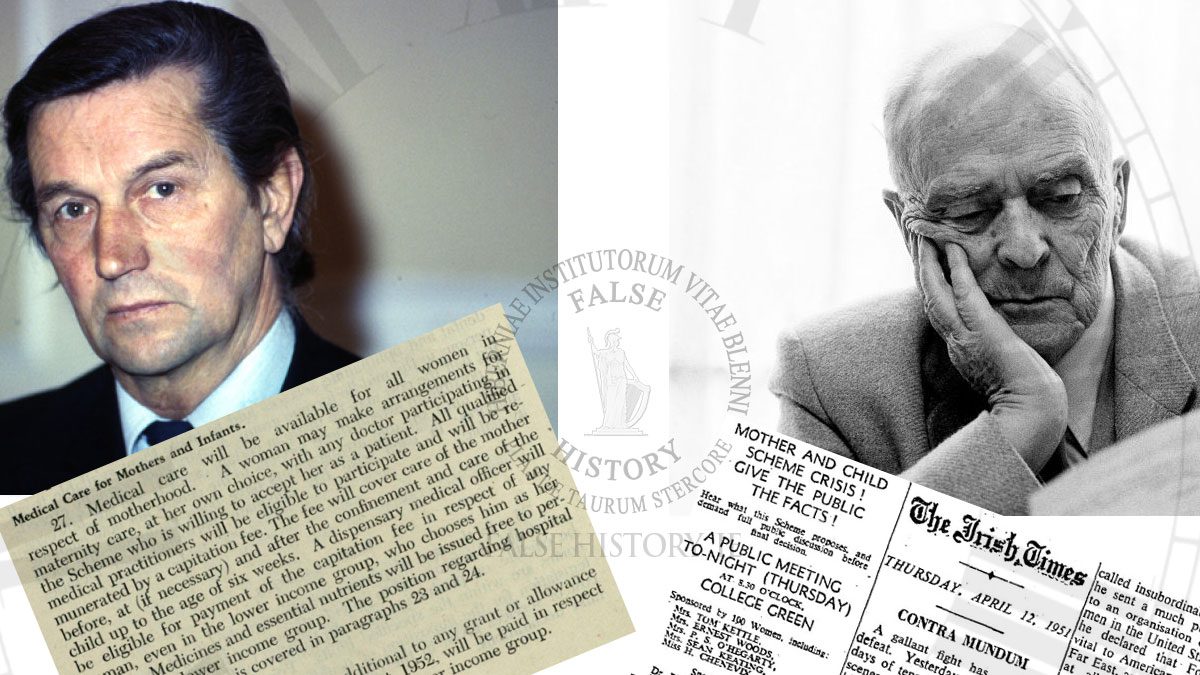

The failure of the infamous Mother and Child Scheme was entirely the fault of Dr Noel Browne, it was not his scheme, nor did the government fall because of it. Yet the myths endure, despite the abundance of contradictory historical evidence, mainly because the story has been subjected to deliberate manipulation. In reality, Browne was a populist politician who was at times delusional, oxygen grabbing, devious, and vindictive towards those he perceived to be his enemies. His political skills were close to non-existent; however, he was gifted with charisma and one great skill, that of turning friends into enemies.

It is often falsely claimed that the failure of the Mother and Child scheme brought down Ireland’s first inter-party government in 1951 and that it was all the fault of the catholic bishops, who had the audacity to interfere in the affairs of the state. It is an enduring anti-Catholic myth, a foundation myth of Irish atheism and its associated anti-clericalism, but sustained mainly due to the Irish cultural obsession with social pretentiousness and poor education.

Browne was Minister of Health under Taoiseach, John A. Costello who remarked:

…that Deputy Dr. Browne was not competent or capable to fulfil the duties of the Department of Health. He was incapable of negotiation; he was obstinate at times and vacillating at other times. He was quite incapable of knowing what his decision would be today or, if he made a decision today, it would remain until tomorrow.

The public never got to view that side of Browne’s personality, to them he was their darling, a man with an alluring persona. He was their champion who was viewed as deeply caring, a man who was on their side, the side of the little people, who possessed the capability and the gumption to challenge the wealthy elite of the country, to improve the lot of the ordinary classes.

Almost paradoxically, Browne had so much charisma that he was initially liked by everyone, and everyone wanted to do business with him and be his friend. However, almost all, including Browne’s most ardent supporters and friends were eventually alienated by Browne, chiefly due to his egotism, a flip flop approach to his promises, his unreliability and his inability to realise that agreements are formed between at least two parties and cannot be changed by one side or the other without agreement.

The Catholic Church has been blamed in popular history for the fall of the Mother and Child Scheme but is a myth that everyone believes to be true. After years of turmoil, when the scheme looked as it was heading for defeat, Browne, then the Minister for Health, made a desperate appeal to the leader of the government, John A. Costello for extra funding for the scheme. On the 13th of March 1951 he urged An Taoiseach to call a cabinet meeting to approve the necessary funds:

If I get the £30,000 I will have the doctors killed on Sunday … but if I do not get the money there will be trouble from the doctors. [1]

The quote evinces, along with the bulk of the evidence, of what group of people Noel Browne, saw as his time, as the principal opponents of the M&C scheme. Moreover, and as John A, Costello was aware, Brown’s figures were grossly in error. The department of Finance had earlier become alarmed when Browne circulated a booklet on the 8th of March, attempting to outflank the doctors, by creating a groundswell of public support, but was full of un-costed detail. It prompted the government’s finance department to calculate the costs which came out at a massive £530,000. They then challenged the officials at the Department of Health to cost the proposals within the booklet, properly. The department officials responded to Finance’s request, estimating the cost to be in the region of £309,000. Even so, Browne was still claiming that his proposals would only cost £30,000, a week after his first approach to the Taoiseach.

The booklet had not been circulated to the government before its public release. Accordingly, no discussion nor agreement had been reached to implement any of the policies outlined in it. Moreover, at the same time adverts, equally not discussed at cabinet level had appeared in the papers, not only extolling the benefits of the new scheme but also lauding the virtues of Noel Browne.

Browne was earlier suspected to be behind a circular which was distributed anonymously in January 1951 to many households in Dublin, particularly around the newly built Corporation estates of working-class Dublin. The document extolled the virtues of the M&C scheme, but its inspiration was revealed through its condemnation of the medical profession, some of whom were described as ‘scum’. The document left no doubt as to who the author or authors thought was to blame for the opposition to the Mother and Child scheme:

Fitzwilliam square would like us to retain the mentality epitomised in the supercilious condescension of the big house charity to the dirty peasant retainers – we will have no part of it.[2] [Fitzwilliam square at that time had about 70 doctors with consulting rooms there.]

The thrust of the document was to promote, in the minds of people, the notion of a wealthy élite who did not want to pay tax as the chief reason for their opposition to the Mother and Child scheme. However, the Bill’s downfall and what was of concern to all sides of the debate was the single issue of a ‘means test’.

Nobody had any objection to anyone who could not afford to pay for their medical care to be treated for free. What made no sense to anyone was giving away expensive healthcare, free of charge, to people who could afford to pay for it. The doctors feared that it would take away a significant proportion of their income but there was far more at stake than meets the eye.

Despite being a medical doctor himself, Browne had managed, from his early days in office, to alienate himself from most members of the profession, and in particular from their representative body, the Irish Medical Association (IMA). He suggested to Costello that the January circular to the people of Dublin was a ‘black propaganda’ exercise conducted by the IMA. This incensed the Minister for Defence, Dr T.F. O’Higgins, who was also a medical doctor and an officeholder in the IMA, labelled the circular, ‘a foul sheet of lunatic liable’.[3] Consequently, he urged the IMA to take action to find out who was responsible for its production.

The IMA hired a private detective who went on to find evidence that pointed to Brown’s close associates. Browne denied any involvement and dissociated himself from the document but significantly did not deny the central charge of being its author. Subsequently, many historians, who are au fait with the historical evidence, believe that Browne was the author.

Moreover, the sentiment it expressed was so consistent with Browne’s beliefs and pronouncements that many of his contemporaries also believed that he was the author. American diplomats based in Ireland relayed their comments on the affair back to Washington, ‘… the embassy has learned on reliable authority that the anonymous document was in fact distributed with the full, prior knowledge of Dr Browne…’[4]

The reality was that the circular was a black operation, perpetrated by Browne, naively thinking he could make it look like a black op by the IMA. It was a feeble and/or an ill-advised attempt, and one which ultimately backfired on Browne. It illustrates the kind of gamesmanship and dishonesty which was a feature of Browne’s time in government and also in his subsequent recollections of events.

Costello was made aware of the outcome of the IMA investigation and expected Brown’s party leader Seán McBride to deal with Browne, but McBride, at that time, was keen to help Browne to side-step the issue of authorship. McBride’s support for Brown in this affair was not due to the fact he believed him concerning whether or not he was the author of the circular, rather he was side-stepping to issue to deal with a much bigger issue, that of a party split. Costello, the master of political compromise, was keen to leave room for the issues to be worked out.

Browne belonged to a small political party that was a component part of Ireland’s first inter-party government. They had only ten TDs in Dáil Éireann which gave them two seats at the Cabinet table. Minister for External Affairs — held by party leader Seán McBride and Minister for Health — held by Dr Noel Browne.

Seán McBride, — who was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace — was a former Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), who founded a new political party called, Clann na Poblachta. Officially launched on 6th July 1946 in Dublin, it fought its first General Election in 1948 on its nine founding principles.

Clann na Poblachta

Foundations

- Elimination of Jobbery, Political preferment and Corruption from public life.

- A Social and economic system based on Christian principles.

- A Comprehensive Social Insurance Scheme on the basis of the Plan drawn up by the most reverent doctor Dignan, Bishop of Clonfert.

- Full employment for full production by equation of Currency and credit to the nation’s needs.

- Nationally financed Non-profit-making Building program for the provision of decent houses for all citizens, and the abolition of slums.

- Immediate reduction in the cost of living achieved by subsidising the production of essential foodstuffs.

- Provision of Sanatoria and facilities for post-sanatoria care for those affected by tuberculosis.

- Free primary, secondary and University Education for all the children of the Nation fitted to avail of it. The raising of the school leaving age to 16.

- Freedom and independence for all Ireland as a Democratic Republic[5]

Emphasis as per the original document.

Clann na Poblachta effectively sold themselves to the electorate as a ‘circuit-breaker’ party, appealing to the masses who were fed up with the slow pace of social and economic reform by insinuating such maladies were all due to political corruption, cronyism, colonial artefacts etc. The Clann stated in public what the people were thinking, and they offered a change from the traditional politics of the day. They had, almost accidentally, struck a chord with the people and went on to win two by-elections in 1947. Their success prompted the ruling Fianna Fáil government to call a snap general election in an attempt to thwart their rise by catching the new party off guard. The plan backfired a little on Fianna Fáil as the Clann, much to their surprise and that of everyone else, won 10 seats.

After the February 1948 General Election, Fianna Fáil was returned as the biggest party but did not have an overall majority. Accordingly, they could only form a government with a coalition partner or as rule a minority government with the aid of a confidence and supply agreement with another party or parties. However, Fianna Fail would not accept a formal coalition arrangement and the opposition parties realised that if they all banded together, and if they secured the support of seven independent TDs, they could form a government. That is exactly what happened, and the Free State got its first inter-party government in 1948.

Fine Gael’s John A. Costello became Taoiseach and the leader of a motley crew with a diverse range of political philosophies, outlook and objectives. Accordingly, it is a testament to his skills and abilities that the government lasted as long as it did.

Dr Noel Browne was attracted to Clann na Poblachta because of the party’s stance on the issue of tuberculosis eradication. He had suffered from the disease himself as a child, had qualified as a doctor and was working with TB patients in a sanatorium. To say he was passionate about the disease and its causal association with poverty, would be an understatement. It was this passion that was to land him a job as Minister over the heads of more senior people within the party. McBride did not realise it at the time, but his appointment of Browne had sown the seeds of resentment, which grew like poison ivy, to not only strangle the fledgeling party but and do immense harm, reputationally, to many people and the nation as a whole.

A significant number of the Grandees of the Clann na Poblachta party were unelectable mainly due to extreme political views including republicanism. Browne would later refer to them as the ‘military wing’ of the party. They opposed the appointment of Dr Browne, — whom they considered of being politically innocent — to the second of the party’s allocation of two cabinet seats.

Con Lehane who had retired from the IRA in April 1938 along with his future party leader Seán McBride, was also elected as a TD in 1948. He fully expected to get the second ministerial portfolio. The selection of Browne by McBride left many within the Clann ‘dumbstruck’. McBride’s personal secretary, Louie O’Brien would later recount that she thought Joe McGrath — who was one of the founders of the Irish Hospital Sweepstakes — provided the impetus for Browne’s appointment. ‘Joe McGrath gave [sic] MacBride £30 million from the Sweeps and McBride had to promise Joe that this will be used only for the elimination of TB’.

TB was a big issue for many political groups and the electorate in general. It had been very much to the fore in the public consciousness because of controversial aspects contained within the 1945 Public Health Bill, specifically, the proposed detention of infectious persons, against their will, in hospitals, compulsory inspections of children etc. Aspects of the Bill were fiercely opposed by all sides for a variety of reasons. Dillon the Minister for Defence personally took a case to the high court to have the forcible detention aspects declared unconstitutional

Accordingly, McBride must have thought that it made sense given the overall political picture to put a doctor who himself had suffered from TB, appointed as Minister for Health.

Resentment concerning Browne’s ministerial appointment from powerful sections of the Clann was only one issue that led to Browne’s downfall. There were many issues left to fester in an apparent leadership vacuum. McBride, as minister for External Affairs, was out of the country on many occasions and had supported issues that were viewed, by some within the party, as going against the Clann’s ethos. He was certainly somewhat out of touch and not on the ground to nip problems in the bud and stop issues from escalating, passively allowing political friends to turn into political foes.

Browne for his part was not communicating with his party leader and this caused McBride to harbour suspicions that Browne was working to undermine his position as party leader. This was indeed the case, Browne’s closest political allies within the Clann became sworn enemies of McBride, and Browne was increasingly under their influence, particularly that of his close friend Noel Hartnett.

Browne has been falsely credited by many people as the best Minister of Health that Ireland ever had. In more recent times, however, many articles have appeared in the newspapers revealing that Dr Brown was one of the worst Ministers for Health in the history of the state. [6]How did this legend come to be believed by so many people and why is it that the truth remains hidden even after 70 years?

Browne lionised himself, taking the credit due to other people for himself. He is the author of his own legend which endures, and remains highly resistant to rational influence, primarily because it instantiates and promotes the chief Irish cultural bias of self-loathing.

Browne remains credited on an RTÉ ‘Brainstorm’ page as ‘the man who did most to eradicate tuberculosis in Ireland and whose Mother and Child Scheme brought down the first inter party government in 1951’, both statements are false in their entirety.[7] He arrived at the Department of Health in 1948 just at the right time when all the heavy lifting had been done. The decision to establish the regional sanatoria — TB super hospitals — was taken in 1945. The seminal 1947 Health Act was in place the year before he came into office. Browne also did not discover the TB wonder drug, streptomycin, but he just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Despite a TB eradication drive being well underway, Browne publicly took the credit for it, while endearing himself to all and promoting himself as a man of action. His TB drive would force all obstacles aside, Browne declared that ‘luxury hotels, set up by the previous government to attract foreign tourists, will be taken over if necessary’.[8]

Browne laid the foundation stone for the first of the regional sanatoria, Merlin Park in Galway but he had no hand, act or part in its establishment or design but has been given the credit in many publications. His need to be seen as a man of action and to feed his vanity, caused him to spend money wastefully on projects like revamping the operating theatres at ‘Woodlands’, the old Galway sanatorium, a mere six months before they were due to close, and the hospital moved up the road to Merlin Park.

When Browne arrived at the ministerial desk in 1948, he found requests for 135 hospital building projects, costing £27m lying on his desk; he reduced this to £15m — to be funded by running down the capital of the Hospitals Trust. By the end of 1949, post-war inflation had raised the costs of the approved building schemes to £26m. According to Marie Coleman, Browne reassured officials that they ‘need not have qualms about the necessary funds becoming available’. Good news for all, because by 1952 the cost had risen to £35.5m.[9]

Browne’s need to claim all the credit for himself is evinced through his removal of senior people from the Department of Health which included the author of the Mother and Child scheme, Dr James Deeny.

Dr Theo McWeeney was the Department’s Inspector of Sanatoria who was suddenly told, without explanation that he was no longer allowed to inspect sanatoria. The Chief Medical Advisor told Browne ‘that Theo knew more about TB than anyone else in Ireland and that with a TB campaign on, it would be short-sighted to take him off TB’.[10] Brown stood firm behind his decision leaving McWeeney aimlessly walking around the department, his distraught demeanour evident to all. He had devoted his entire career to the disease and was a world-renowned expert on TB. He applied to the World Health Organisation and was quickly snapped up and put in charge of the TB eradiation schemes in eight countries in Southeast Asia, with a population of over one billion people.[11]

Dr James Deeny was the Chief Medical Advisor to the government since 1944 and was the author of the Mother and Child scheme, played a significant role in both the establishment of the regional sanatoria and in authoring the 1947 Health Act along with Dr Con Ward. Deeny is, more than anyone, is entitled to claim the title of ‘the man who did most to eradicate tuberculosis in Ireland’[along with Con Ward and the team at the Department]. Deeny is unknown to the public because all his oxygen was taken by Browne. Browne got rid of Deeny from the department but fortunately, he returned to his position in the aftermath of Brown’s demise.

Deeny recalls meeting Browne for the first time at Newcastle Sanatorium where he worked:

He had gone as far as he could go in Newcastle and was about ready to burst out somewhere, some place or in some way. At the same time, he was intolerant, begrudging of other’s efforts and while a magnificent destructive critic, which at that time was easy, he had few constructive or practical ideas. However, he was likeable, certainly compassionate and had a lot going for him.[12]

Shortly after Browne’s appointment as Minister for Health, Deeny tells of an incident that typifies Browne’s, Achilles Heel. Deeny suggested to him that he give a speech at an upcoming event at the Royal College of Physicians, which would give him a good opportunity to introduce himself to the doctors. The event was on the subject of Irish medical history and as Browne had no knowledge of this history, so Deeny wrote the speech for him.

However, when Browne got halfway through his speech, he folded up the papers and placed them in the inside pocket of his jacket. He then, inexplicably and without cause, launched into what was described as a vehement and violent attack on the doctors. After Browne resumed his seat, each and every speaker after that launched an equally vehement and violent attack on Browne. Browne had made a mistake of epic proportions, aliening himself from the very people whose support he would need to get anything done. Sadly, this was typical of Browne, in certain situations, he could not control his temper, especially in the company of people he himself held as contemptible, possible evidence of plutophobia.

Deeny heard of the schemozzle the following morning and told Browne with words to the effect, that he would not achieve his aims by berating people. They will simply clam up and resist everything and anything you would try to do. Deeny told him of Dr Ward, the former parliamentary secretary with responsibility for health matters, who had ‘a tendency to be aggressive and as a consequence had a tough time with his health bill, while James Ryan took things easily and had little medical opposition to the 1947 Act’.[13] Deeny surmised that his simple act of relaying the truth to Browne would not go down well with the imperious minister. Accordingly, he sat back and waited for the inevitable.

The inevitable arrived in the form of Mr O’Cinneide, the Secretary, from Brown’s office. He politely offered the Chief Medial Advisor an appointment to ‘take over St James’s Hospital’ and turn it into a world-class facility. Sideways promotion was the closest action available to a minister who wanted rid of senior officials. Deeny refused the job but proposed an alternative position. He had for some time wanted to do a national survey of TB. He was swiftly seconded to the Medical Research Council and given an office, well away from the Department of Health. Unlike ordinary surveys, medical surveys, such as the one Deeny undertook, are the foundation stone of epidemiology, helping to document the causes of diseases spread and looking at ways of mitigating their progression through society.

Significantly, and despite its importance, Browne had no interest in the workings, its progress or the findings of this survey.[14] Its aim was only to get rid of Deeny, and so Browne, at last, reigned supreme, he was now the government’s de facto Chief Medical Advisor and its leading TB expert.

It appears that Browne had surrounded himself with ‘yes men’, carefully selected so as not to take any glory away from Browne. His isolation meant he had no proper guidance and unbeknown to himself, was on a slippery slope to disaster. James Deny wrote:

Browne had insufficient negotiating experience, not enough knowledge of the subject matter of Maternity and Child Welfare, without guidance and restraint from the cabinet, party or leader, all of whom he seems to have alienated and depending on the medical profession who he had antagonised.[15]

There is an international dimension to the controversy which barely gets any attention. These events occurred at the start and early days of the Cold War when the prospect of a Communist takeover of Europe was a real and present fear. Fianna Fáil had been at the forefront in labelling Clann na Poblachta as a communist organisation. Many people feared the communists, none more so than the church who feared the same persecution, mass murder of Christians and forced conversion to atheism as had occurred in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, would occur here. The antics of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party had also tainted the word ‘socialism’ with many negative connotations. In one example Fianna Fáil’s Sean Lemass warned that Ireland was ‘on the list for attack in the campaign now being waged to destroy Christian democracy in Europe`. William Norton, the leader of the socialist Labour Party, keen to distance itself from communism, spoke at an election rally on 22 January 1948, and referred to Communism as a ‘pernicious doctrine… detestable to the Irish people, who prized religious liberty and freedom of conscience`.[16]

Such fears were not Ireland’s alone, Winston Churchill viewed attempts to introduce a National Health Service (NHS) in Britain ‘as first step to turn Britain into a National Socialist economy’. The Conservatives voted against the formation of the NHS no less than 21 times.

Aneurin Bevin’s attempt to introduce a national health service in Britain was met with fierce and sometimes bitter opposition. Many battles were fought between the government, charities, churches and local authorities against the formation of the NHS. The most common grievance was that they did not want the state taking control of their hospitals, while an overwhelming number of doctors did not want to become state employees. ‘Socialised medicine’ is the phrase to describe plans like Bevin’s and this phrase also took on board many negative connotations. In the end, the NHS could not work without doctors and so Bevin and the government was forced to compromise. General Practitioners remained as private businesses given public contracts to provide healthcare.

For us today, the eventual establishment of the NHS in Britain masks somewhat how fierce the opposition was to it in the first place. One former chairman of the British Medical Association commenting on the Bill in 1946 describe it thus:

“I have examined the Bill and it looks to me uncommonly like the first step, and a big one, to national socialism as practised in Germany. […] The medical service there was early put under the dictatorship of a “medical fuhrer” The Bill will establish the minister for health in that capacity.”[17]

In the two years from 1946 to 1948, the BMA fought a fierce campaign of opposition and in one of their polls claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service.[18]

Many Irish doctors also feared ‘socialised medicine’ and were equally determined that the ‘defeat’ which had happened to doctors in Britain would not happen in Ireland.

The international dimension may be forgotten now, lost in the fog of anti-Catholic myths but it was very much to the fore at that time. Noel Browne’s former party colleague and supporter, Peadar Cowan, during the Dáil debate on Noel Browne’s resignation, told the Dáil:

It was inevitable, in the introduction of such a scheme, that there would be difficulties between the Minister for Health and the doctors. They had those difficulties in Britain, very serious difficulties, between their Minister for Health and the doctors and the fight was fought as bitterly there as it was fought here. I thought that the fight would resolve itself in the way it did in England, that the doctors who had been most opposed to the scheme would find that it was as beneficial for them as for the community.[19]

Emphasis is mine

The political situation in Britain was very different. Bevin was in a strong political position with the backing of a party who had come to power defeating the Conservative Party under Winston Churchill by a landslide. Unlike the situation in Ireland, he did not have the added difficulty of having to manage a menagerie of politicians united in a shaky coalition, where the dissatisfaction of a small number of politicians, had the potential to bring down the government down. This is is what happened, however, to dispel another myth, it was not Browne who brought down the government!

Moreover, the single issue which had everyone up in arms and ultimately upon which the Mother and Child scheme fell was the issue of the means test. The primary purpose of the scheme was to give free health care to all mothers and children regardless of their ability to pay. The inclusion of ‘all’ frightened the medical profession who opposed the scheme because it would threaten their income plus other concerns.

James Deeny, the author of the scheme, proposed that no means-test be applied so to remove any stigma of pauperism attached to it. In other words, many women would have been put off participating in the scheme for fear of been seen as paupers. The sense of human dignity, which we all have, would cause people to hold off on entering the system, often to the detriment of their health. This was a time when the living memory was fresh of the despised workhouses of British rule. Many destitute people died rather than face the ignominy, dehumanising regime and parsimonious so-called charity of the landlord class.

Deeny, ahead of his time, was advocating what is now called today ‘universal entitlement’, every woman and child would be entitled to claim the scheme’s benefits, regardless of their financial circumstances, accordingly, there would be no stigma. It is a percept widely accepted today in payments like the children’s allowance. However, ‘universal entitlement’ has a significant cost and most such schemes lay in the future.

The British introduction of the NHS in 1948 is often used by Irish history writers to engage in their favourite pastime of self-loathing and berating the Irish. The chief claim is that Ireland should also have introduced a universal health scheme at that time. It a counterfactual reliant on a lack of knowledge and the result of an education provided by the Walt Disney company. It relies on a completely false comparison of the richest and most industrialised nations on earth to one of the poorest, unindustrialised nations on earth, berating the poor for being unable to spend like the rich.

What little industry Ireland had was lost on independence as it was located within Northern Ireland. It was the result of centuries of economic neglect under British rule which could not be reversed for decades. Most Irish people are not taught their history and do not realise just how badly Ireland was bled dry through over taxation and its wealth invested in Britain, not Ireland. For example, the British spent £8 million on famine relief in Ireland during the 1940s but spent £100 in fighting a war with Russia in 1852-3, which Ireland was made to pay more than its fair share. The process began shortly after the Act of Union Ireland when Ireland was forced to pay for Britain’s involvement in the Napoleonic Wars. It caused the Irish treasury to go bust. These issues were very well known to the Irish populace in the 1930s and 40s, not least, because de Valera had raised these issues when the Irish government withheld the Land Annuity payments to Britain sparking the Economic war.

Political piousness/idealism does not often lend itself easily to practical governance. The new party of Clann na Poblachta saw itself as offering the electorate a new form of politics, a party with the number one priority for the ‘elimination of jobbery, political preferment and corruption from public life’. Noble, laudable and achievable as such promises are, McBride silently — ultimately to detrimental effect — added patronage to the list. There is a simple rule for rulers, which has existed from time immemorial, that the generals and foot soldiers must be rewarded for their service. Otherwise, their support cannot be relied upon on an ongoing basis.

McBride, as we saw earlier, failed to give the second seat to Con Lehane but he also failed to give Noel Hartnett, a senate seat which he had also half-expected. Hartnett, as the Director of Elections for the Clann, was the mastermind of the party’s electoral success. He was a strong supporter of McBride but slowly his disappointment progressed, first towards disillusionment, before ending up as open hostility. Hartnett was always a supporter of Noel Browne but as his hostility towards McBride grew, it must have also reinforced in McBride’s mind, that Noel Browne was also working with Hartnett to undermine his position as party leader.

In November 1949, Sean McBride invited Noel Browne to dinner at the Russell Hotel to discuss with him, on a one-to-one basis, issues internal to the party, in an attempt to get to him before Noel Hartnett. He was too late. Browne made it clear that he was trying to embarrass McBride, both in private and in public, to force him to act on the Mother and Child Scheme, and that if McBride did nothing he would resign and bring down the government. McBride wrote at the time ‘now that I knew the truth I should ask him for his resignation and appoint a new minister for health’.[20] McBride was now aware of what was happening within Hartnett’s and Browne’s section of the Clann and began to work on a strategy to confront Browne within the Clann. McBride circulated all his cabinet colleagues with his account of the meeting with Browne, so now the government and the Taoiseach were aware of what was going on within the Clann. So too were the doctors who circulated a questionnaire to their members to elicit a hostile response to which Browne took exception.

By the end of November, Costello now felt he should try and defuse the situation by mediating between Browne and the doctors. Browne took Costello’s intervention to be an undermining of his negotiating position, — he later apologised for holding this view — while Costello learned for the first time of the strength of feeling that the doctors held in their opposition to the scheme. Browne’s failures were now obvious to his cabinet colleagues and the danger they possessed to the survival of the government. Browne’s resignation alone would not be enough, but if Browne succeeded in ousting McBride, he might also take the Clann out of government.

By January 1951 the Mother and Child Scheme was of secondary importance as Browne’s primary objective became — as John Horgan put it — ‘the political burial of the Clann and its leader’.[21]

Browne resigned from the Clan’s standing committee but not from the Cabinet, while on the same day Noel Hartnet from all his positions in the party and from the party itself. Neither Browne nor Hartnett mentioned the Mother and Child Scheme as a reason for their resignations. McBride tried to stem rumours of a split within saying that, ‘there was an attempt at the Palace revolution — led by our friend N. H. It failed. He resigned. His resignation was unanimously accepted’.[22]

McBride’s first big counter-attack, within the Clann, took place on the night of the 31st of March. It passed two resolutions:

The first reiterated the executive support for Browne’s scheme, but expressed its fear that the successful implementation of the service may be jeopardised by the manner in which the whole problem was being handled by Dr Browne; the second expressed its grave concern and disapproval at Browne’s attitude and conduct, and called him to show greater loyalty and cooperation.[23]

Various attempts were made to mediate with Browne but all were to no avail, and not even given any kind of serious consideration by Browne. Some of the many attempts include one by William Norton, the leader of the Labour Party, prompted by both Costello and McBride attempted to instantiate a compromise by suggesting that the scheme would be limited to families with an income of under £1000 a year. Yet another attempt was made by the Trade Union Council (TUC), which suggested that women should pay ten shillings to secure their entitlements under the scheme.

Browne’s stubborn refusal to listen to reason meant he was now on the cusp of getting fired, which in parliamentary terms, happens when the Taoiseach calls for a minister’s resignation. His plan to politically undermine McBride and destroy the Clann had not worked and so in a final act of desperation, he tried to turn public opinion against the government. It appears his strategy was based on the hope that when the government fell, the main issue in the ensuing election would be the Mother and Child Scheme, and so he could get it through the succeeding parliament by popular demand.

Normally the Taoiseach requests a minister to resign but on this occasion, the Taoiseach deferred to Browne’s party leader. McBride wrote formally to Browne requesting his resignation on the 10th of April 1950. It was hand-delivered to Browne at the Customs House. Brown issued his letter of resignation the same day but effective from the following morning. That night, Browne and his accomplices took to destroying files at the Customs House, an act, which John Horgan described as ‘inexcusable’ and ‘historical vandalism’. [24]

Browne, Hartnett and Brian Walshe were later observed at Browne’s home assembling letters for publication in the national newspapers, especially the Irish Times, a favourite conduit of Brown’s opinions. Bertie Smyllie, the editor was a staunch supporter of Browne but his newspaper was far from the Irish Times we know today. The paper at that time had a small circulation of only 30,000, and despite nearly 30 years of independence, remained staunchly biased towards the protestant and unionist perspective.

Browne published the correspondence between himself and the bishops. Recently, while marking the 70th anniversary of Browne’s resignation, the Irish Times boasted of its role:

On April 12th, 1951, under the front-page headline Minister Releases Correspondence, The Irish Times reproduced the full text of the letters, the most telling of which, dating from October 1950, was a letter from the hierarchy to taoiseach [sic] John A Costello. It described Browne’s scheme as “a ready-made instrument for future totalitarian aggression”, declared that the “right to provide for the health of children belongs to parents, not to the state” and noted that “education in regard to motherhood includes instruction in regard to sex relations, chastity and marriage. The State has no competence to give instruction in such matters”.[25]

Every tin-pot and barstool historian, journalist, bloggers, crackpot feminists and the full menagerie of axe grinders, all chose to ignore the totality of the historical evidence and point the finger of blame, for the failure of the Mother and Child Scheme, solely at the catholic church. They are encouraged in this view by Noel Browne through his many subsequent media appearances and his autobiography. Historians who are au-fait with the controversy and maintain an impartial disposition, all agree that Brown’s version of events is incongruent with the evidence and the truth.

The demonisation of Archbishop McQuaid in popular history is largely due ‘to Browne’s own single-minded bitterness in later years against John McQuaid’[26]. Browne’s anti-clericalism is only evident from the 1960s but his explosive temper, bitterness, vindictiveness and his strange way of doing business were evident long before he entered politics.

James Deeny recalls that towards the end of 1946 a group had asked to meet with him.

The group [Superintendents of Sanatoria] came in with Noel Browne as Secretary; I outlined the [TB] scheme to them and made a general presentation on the subject and produced the plans for the [new regional] sanatoria for their criticism and advice. The discussion proceeded pleasantly until Browne took over. He made a lot of scathing remarks and was downright rude and insolent. Now I had stuck my neck out on this thing [the TB scheme], had taken it in hand, got it going and was producing results. So I was not about to take calculated rudeness from a young sanatorium assistant, no matter how able, whose experience was extremely limited and whose remarks anyway were not helpful. Since he continued and no one could stop him, I terminated the meeting.[27]

McQuaid and others might have acted differently had they known the type of person Browne was. On one hand, he appeared to be an extremely charming man, a passionate advocate for his cause. On the other hand, there was a man who impossible to do business with.

Browne met with McQuaid, two other bishops in October 1950, an important meeting which left Browne with the mistaken impression that he had assuaged their fears. Browne was perhaps not listening and gave himself the impression that the main objections of the bishops were in the area of education and missed entirely that their most fundamental objection — held in unison with the doctors — was the lack of a means test and the associated fear of it as creeping towards communism.

The bishops wrote a reply to Costello outlining their objections which Costello passed on to Browne in November some weeks after the date on the letter. Browne made the assumption that Costello passed the letter to him out of courtesy and perhaps did not study it carefully, content in the knowledge that he had the bishops onside. He had his secretary Paddy Kennedy prepare a lengthy memorandum in response, it is significant for it evinces that both Browne and his Department missed the fact that the means-test represented the fundamental objection of the bishops. He gave the memorandum to Costello to use as the basis of the Taoiseach’s reply. Costello did not pass it on, as he felt it would be premature given that negations were still ongoing. Browne claimed to have been unaware that it had not been sent, while Costello stated that he had told Browne many times orally that he had not sent it. In any case, it appears that Browne genuinely believed that the only remaining enemies of the Mother and Child Scheme were the doctors, hence his desperate plea in mid-March 1951 for £30,000 to ‘have the doctors killed on Sunday’.

The Mother and Child Scheme didn’t need much selling but the free-for-all, no means-test element would be very hard to sell. The scheme’s author, James Deeny, knew this was the case and was in the course of preparing the groundwork for its acceptance by the church. That was, until, in his words, Noel Browne, ‘butted in and spoiled everything’.

Every salesperson is taught to deal with customer objections, which are issues that customers raise in response to a sales pitch. Common objections include, ‘it’s too expensive’, ‘I can buy it cheaper online’, ‘I can get it cheaper at your competition’ etc. Sales professionals are trained to anticipate such objections and have a prepared response ready to deploy during every sales pitch. It involves a thorough knowledge of the product and its competitors while matching the customer needs to the right product through ascertaining what their needs are. Or if they are unaware of their needs, showing why they need a particular product.

James Deeny or ‘Jet’, — the nickname he acquired for the speed of how quick he could get things done — anticipating the ‘customer objections’, had gathered the evidence for similar health improvement schemes in the United States, which had been enthusiastically adopted by Catholic dioceses there. Deeny was working on implementing his Mother and Child Scheme since 1946, first, he had secured the enthusiastic backing of the Masters of three of Dublin’s biggest maternity hospitals. Later the scheme was rolled out to maternity accommodation at district hospitals and other institutions. Education was another cornerstone of the Mother and Child Scheme as high infant mortality rates, were at that time, blamed on the ignorance of the mother. Deeny and his team set about devising and implementing a course to teach hygiene and healthy living habits to school children, both boys and girls. He successfully sold the scheme to the heads of various catholic secondary schools, who embraced the scheme with enthusiastic support, especially after they saw American books on the subject, complete with the imprimaturs of their Cardinals and Archbishops. However, the scheme had no funding nor legal basis, so John Garvin drafted a section to be included in the 1947 Health Bill. This was the section that was to provoke all the controversy.

The Bill contained a strong measure of ambiguity as to what exactly was going to be taught but there was no ambiguity about the level of power the bill would give to minister to make decisions across the board, even to set the education agenda, and do so without consultation with the various stakeholders. The Catholic Hierarchy feared that the policy could be used to promote ideas contrary to its teachings. Deeny says that the clergy were not initially against the idea of health education, that is ‘until the medical politicians inspired their opposition’.[28]

Deeny’s point is significant, the doctors used the hierarchy to their advantage, they got the bishops excited and took a back seat and watched events unfold. Many years after the affair Donal Herlihy, Bishop of Ferns, put it bluntly: ‘we allowed ourselves to be used by the doctors, but it won’t happen again’.[29] However, the reality of the situation was that there was no way on earth that Browne was going to be able to force through the bill, even if all the bishops’ objections had been assuaged.

Browne’s failures are often blamed on his inexperience as a politician. On one hand, he had the great skill of a politician, that of taking the credit for other people’s achievements, but on the other, he did not have negotiation skills and could not compromise. Compromise is the lifeblood of politics and eventually, the Mother and Child Scheme was implemented by arriving at a compromise between all the stakeholders.

After he fired Browne, Costello took over as Minister for Health and set about repairing the damage and seek out compromise proposals. However, the compromise would eventually be worked out by his successor as Minister for Health, Dr James Ryan under the subsequent Fianna Fáil government. He too tried to implement the 1945 Mother and Child Scheme but ran into the same difficulties as Noel Browne. Ryan, however, sought the advice of Deeny —who was yet to return to the Department as Chief Medical Advisor, now that Browne was gone. He advised that medical research had shown that it was the children of the poor who suffered from the highest mortality rates and poor health. Reducing the ‘poverty health penalty’ was at the heart of his scheme and so the stage was set for compromise and finally, the Mother and Child Scheme was incorporated into the 1953 Health Act. Deeny said:

In the end we got more or less what we wanted. […] The new scheme gave women a choice of doctor and we arranged at the antenatal service should be a fee-for-service basis, set a decent level, so that the doctors got paid properly for anything they did were likely to work hard to popularise the service since it was to their benefit as well as to the patient.[30]

There is much more to the story than just doctor Browns political inexperience. As I quoted earlier, John A Costello has a valid point when he stated in the Dáil that ‘Deputy Dr. Browne was not competent or capable to fulfil the duties of the Department of Health’. Sean McBride also pointed to the peculiarity of Browne’s behaviour telling the Dáil chamber that, ‘for the last year, in my view the Minister for Health has not been normal’.

To which Oliver J. Flannigan replied, ‘is that an insinuation that the Minister is insane?’

McBride: ‘Might I qualify that —normal, in the sense that he has not behaved as any normal person would behave or be expected to behave.’ [31]

It is worth repeating at this juncture Dr James Deeny astute and direct as comment as it leaves no room for doubt where the blame for the failure of the Mother and Child scheme lay:

Browne had insufficient negotiating experience, not enough knowledge of the subject matter of Maternity and Child Welfare, without guidance and restraint from the cabinet, party or leader, all of whom he seems to have alienated and depending on the medical profession who he had antagonised.[32]

John A. Costello put it more bluntly:

I and my colleagues, particularly Mr. Dillon, Dr. O’Higgins, the Tánaiste [Norton] and myself, were doing everything we could to avoid a disedifying and disreputable clash ensuing between the Minister for Health, because of his obstinacy, and the medical profession.

Dr. Browne has had the start of a whole day to make his allegations, and no matter what I do I shall never catch up with him to the end of my public life, and certainly not in respect of that newspaper [the Irish Times]to which I have already referred the infinite capacity of Dr. Browne for self-deception.[33]

Costello was right, his view never caught up with Noel Browne, at least in the eyes of the public. He could have quoted the great Irish writer Jonathan Swift:

Besides, as the vilest Writer has his Readers, so the greatest Liar has his Believers; and it often happens, that if a Lie be believ’d only for an Hour, it has done its Work, and there is no farther occasion for it. Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it; so that when Men come to be undeceiv’d, it is too late; the Jest is over, and the Tale has had its Effect…[34]

It is still common to find stories in the Irish media perpetuating another associated falsehood, that Mother and Child Scheme brought down the government. Browne was fired on the 11th of April but the government was not dissolved for nearly two months. While the health crisis was ongoing there were many other issues affecting the government like nationwide Bank Strike and Rail Strikes which had contributed to the ongoing Cost of Living crisis. When Costello dissolved the Dáil on the 30the of May 1951 it was over the issue of agriculture, not health.

James Dillon, the Minister of Agriculture, had refused to raise milk prices which were fixed by the government using the Milk (Retail Price) Order, 1950. Patrick O’Reilly TD speaking in the Dail in March 1951 outlined the grievance, price increases were necessary to ‘give farmers the cost of production and a reasonable profit’.[35] At the end of April, as a direct result of Dillon’s refusal to raise prices, the government lost the support of three independent TDs Patrick Cogan, Patrick Lehane and William Sheldon. Two more, Patrick Finucane and Patrick Halliden resigned from Clann na Talmhan in protest at the way Dillon had treated milk producers. However, the Independent farmer TDs who had supported the Government in the past were prepared to continue doing so—if the price paid to milk suppliers was increased. ‘As Dillon’s biographer Maurice Manning has written, the collapse of the Government’s support had far more to do with agriculture than it did with the Mother and Child Scheme.’[36]

There is absolutely no doubt that Browne’s political and medical contemporaries were of the view that the failure of the scheme was entirely due to Browne’s failings.

Astonishingly, the Brown legend continues to circulate unchallenged, flying in the face of the truth, even within certain academic circles, especially among those who, as students, spent too much time in the college bar.

The state broadcaster RTÉ, as we saw earlier, carries false claims on its ‘academic’ section of its website. The station has acquired a particularly pernicious anti-Catholic bias in recent decades and has been rewriting into history with many fabrications, ranging from the Cavan Orphanage fire to Fr Kevin Reynolds, to the Mother and Baby homes, and more.

The Irish media, in general, has also continued to attack the catholic church, again mainly using falsehoods dressed up as evidence. It all, however, has its genesis in the legend of the Mother and Child Scheme of the 1950s.

Brownnosing is the colloquial term for an act or acts designed to ingratiate oneself to another. In other words, it is one of the methods used by people to make themselves likeable. In Irish society, Browne-nosing has a similar meaning where people ingratiate themselves to others by using fables. Anti-catholic fables are most in vogue these days.

Written by Eugene Jordan, 30 May 2021, marking the 70the anniversary of the dissolution of the first inter-party government in 1951.

Number 4 will appear next month.

References

[1] An Taoiseach, John A. Costello, Oireachtas, ‘Adjournment Debate—Resignation of Minister. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Thursday, 12 Apr 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’.

[2] Horgan, Noel Browne: Passionate Outsider.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Clann Na Poblachta Dublin South Central Constituency.

[6] Gueret, ‘Ireland’s Best and Worst Health Ministers’.

[7] Breathnach, ‘How the Irish Government Fought the TB Epidemic in the 1940s’.

[8] Horgan, Noel Browne: Passionate Outsider.

[9] Daly, ‘The Curse of the Irish Hospitals Sweepstake: A Hospital System, Not a Health System’’.

[10] Deeny, To Cure & to Care: Memoirs of a Chief Medical Officer.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Horgan, ‘Anti-Communism and Media Surveillance in Ireland 1948-50’.

[17] Broxton, ‘Why Should the People Wait Any Longer? How Labour Built the NHS’.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Oireachtas, ‘Adjournment Debate—Resignation of Minister. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Thursday, 12 Apr 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’.

[20] Horgan, Noel Browne: Passionate Outsider.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] O’Brien, ‘How The Irish Times Exposed the Mother and Child Scandal 70 Years Ago Today’.

[26] O’Kelly, ‘Shedding New Light on the `wayward’ Dr Browne’.

[27] Deeny, To Cure & to Care: Memoirs of a Chief Medical Officer.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Horgan, Noel Browne: Passionate Outsider.

[30] Deeny, To Cure & to Care: Memoirs of a Chief Medical Officer.

[31] Oireachtas, ‘Adjournment Debate—Resignation of Minister. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Thursday, 12 Apr 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’.

[32] Deeny, To Cure & to Care: Memoirs of a Chief Medical Officer.

[33] Oireachtas, ‘Adjournment Debate—Resignation of Minister. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Thursday, 12 Apr 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’.

[34] Swift, The Examiner.

[35] Oireachtas, ‘Committee on Finance. – Adjournment Debate—Price of Milk. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Tuesday, 6 Mar 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’.

[36] McCullagh, John A. Costello The Reluctant Taoiseach: A Biography of John A. Costello.

Bibliography

Breathnach, Ciara. ‘How the Irish Government Fought the TB Epidemic in the 1940s’. Media Website. RTÉ – Irish State Broadcaster, 23 March 2020. https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2020/0323/1124818-ireland-tb-epidemic-coronavirus/.

Broxton, Anthony. ‘Why Should the People Wait Any Longer? How Labour Built the NHS’. British Politics and Policy at LSE, 2017.

Clann na Poblachta. Clann Na Poblachta Dublin South Central Constituency: Election Poster. Dublin: Darragh Connolly, Solicitor, Election Agent for the candidates, 1948. http://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000644873.

Daly, Mary E. ‘The Curse of the Irish Hospitals Sweepstake: A Hospital System, Not a Health System’’. Work Papers Hist Policy 2 (2012): 1–15.

Deeny, James. To Cure & to Care: Memoirs of a Chief Medical Officer. Glendale Press, 1989.

Gueret, Maurice. ‘Ranked: Ireland’s Best and Worst Health Ministers’. Irish Independent. 23 January 2017. https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/news/ranked-irelands-best-and-worst-health-ministers-35391561.html.

Horgan, John. ‘Anti-Communism and Media Surveillance in Ireland 1948-50’. Irish Communication Review 8, no. 1/4 (2000): 30–34.

———. Noel Browne: Passionate Outsider. Gill and McMillan, 2000.

McCullagh, David. John A. Costello The Reluctant Taoiseach: A Biography of John A. Costello. Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 2010.

O’Brien, Mark. ‘How The Irish Times Exposed the Mother and Child Scandal 70 Years Ago Today’. The Irish Times. 12 April 2021. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/how-the-irish-times-exposed-the-mother-and-child-scandal-70-years-ago-today-1.4524235.

Oireachtas, Houses of the. ‘Adjournment Debate—Resignation of Minister. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Thursday, 12 Apr 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’. Text, 12 April 1951. Ireland. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1951-04-12/43.

———. ‘Committee on Finance. – Adjournment Debate—Price of Milk. – Dáil Éireann (13th Dáil) – Tuesday, 6 Mar 1951 – Houses of the Oireachtas’. Text, 6 March 1951. Ireland. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1951-03-06/33/.

O’Kelly, Emer. ‘Shedding New Light on the `wayward’ Dr Browne’. Independent. 29 October 2000. https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/shedding-new-light-on-the-wayward-dr-browne-26257006.html.

Swift, Jonathan. The Examiner. 15. London: Printed for John Morphew, near Stationers-Hall, 1710.