A major discovery at the former Tuam children’s home has finally driven a stake through one of the most corrosive falsehoods of modern Irish public life: the claim that 796 children were disposed of in a septic tank.

This article links directly to primary source maps, planning documents, and official statements for independent verification.

On Friday, 6 February 2026, the Office of the Director of Authorised Intervention confirmed that infant remains were discovered beneath the driveway leading to the present-day cemetery at the Tuam site. The remains date to the period when the institution operated as a children’s home, before its closure in 1961 and demolition in the early 1970s to accommodate a local authority housing estate.

The detail that matters, the detail that collapses an entire narrative, is this: all thirty-three infants recovered to date were buried in coffins.

This is not an incidental finding. It is conclusive.

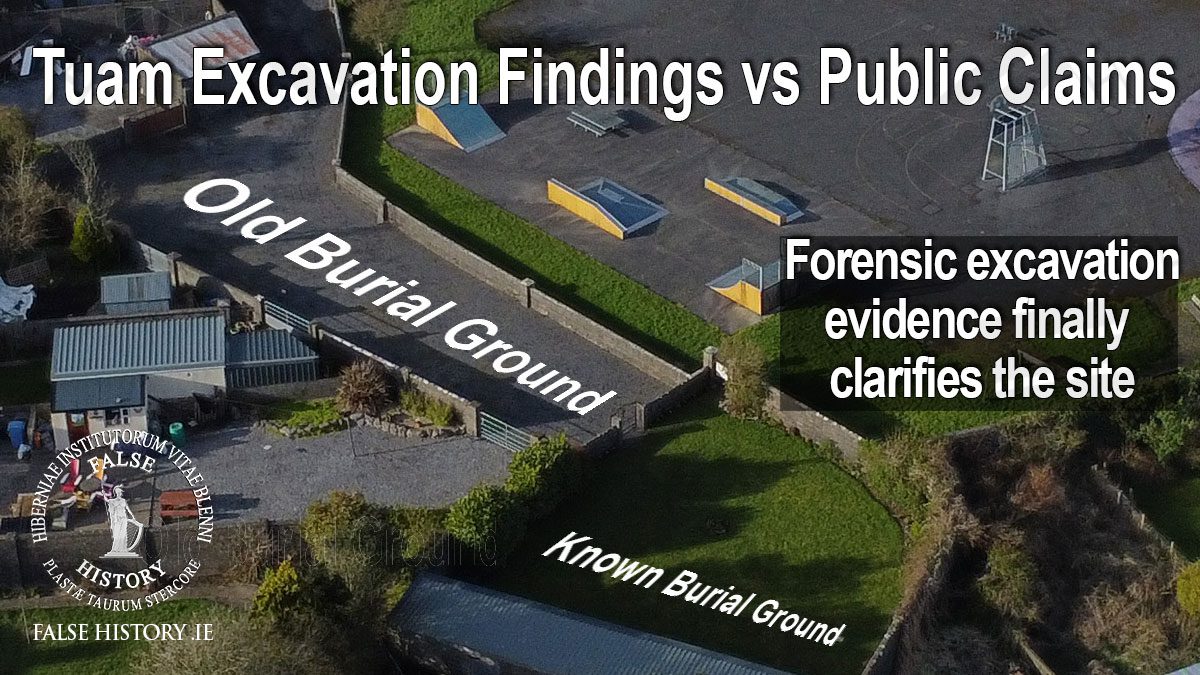

Historic maps show, with complete clarity, that the children’s burial ground extended far beyond the small area that has been publicly acknowledged for years. Yet a driveway, now servicing the rear of surrounding houses, was laid directly across part of that mapped cemetery. The latest findings confirm what the maps always showed: the burial ground was substantially larger, and later construction intruded directly into it.

Crucially, Galway County Council possessed those maps at the time. As owner of the former children’s home, the Council oversaw the development of the housing scheme, approved under plans explicitly titled Galway County Council, Tuam Housing Scheme (Extension), Site Layout. The documentary trail leaves no room for ambiguity. Evidence of the burial ground’s full extent existed while works were authorised and supervised that encroached upon it.

This is not a new conclusion. In 2014, at the height of the most extreme allegations, including claims of murder, Garda investigators examined the site. On the basis of historic maps and physical inspection, they concluded that the burial ground was approximately three times larger than the area then recognised, with sections extending into the rear gardens of houses along the Athenry Road. No criminality was found. The maps spoke for themselves.

Former archaeologists active during the 1970s have since acknowledged an uncomfortable reality: the destruction of archaeological and burial sites during that period was routine. Ringforts were levelled. Famine-era pauper graves were built over. Small graveyards vanished under concrete. Human remains were frequently uncovered during construction and handled informally, sometimes reinterred, sometimes discarded, because delays were inconvenient and oversight minimal. The instruction was simple: get on with the job.

Against that backdrop, the discovery of infant burials beneath a housing estate driveway is not shocking. It is entirely consistent with the historical record and with known construction practices of the era.

Burials have now been identified at the outer limits shown on the historic maps. The absence of remains in adjoining areas raises a stark possibility: that bones were disturbed during construction, removed, discarded, as local people have long claimed, or reinterred elsewhere, possibly beneath concrete structures later incorporated into the modern memorial garden.

The precise mechanics may yet be clarified. But one fact is no longer open to dispute: construction works intruded into a burial ground that was already known to exist. Responsibility therefore lies not with a defunct institution, but with those who authorised and executed that development, contractors, officials, or both.

The wider implications are devastating for the narrative that dominated public discourse for a decade. Of the 796 children whose deaths were recorded at Tuam, 33 have now been confirmed as buried on site in a dignified manner. The remainder have been demonstrably shown not to have been disposed of in a septic tank, and not to have been subject to the grotesque claims of “disrespectful” burial that were repeated as fact.

As excavation continues, scrutiny will intensify. But it will not fall where many expected. Increasingly, it will turn toward those who promoted claims that collapsed the moment evidence, not slogans, were allowed to speak.

Truth has a habit of surfacing. Even when someone builds a road over it.

EJ

Sources

Technical Update from the forensic excavation at the site of the former Mother and Baby Institution in Tuam, Co. Galway

Friday, 6th February 2026

https://odait.ie/news/technical-updates/technical-update-5/

Extract

Hand excavation continued under the cover of the tent. As outlined in the previous Technical Update, this area was identified in historical documents as a “burial ground”. The recovered evidence from this area is consistent with it being a burial ground from the time of the operation of the Mother and Baby Institution.

ODAIT references the fifth interim report of the commission of investigation into mother and baby homes…

Footnote: Referenced by the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation (MBHCOI), see paras. 8.11 to 8.50, Fifth Interim Report, MBHCOI, 2019, and reproduced (table 1.2 of Appendix A of Fifth Interim Report, MBHCOI, 2019).

Available here:

The text of Section 8.38

In 2014, An Garda Síochána conducted an investigation. The documentation collected and the analysis done were provided to the Commission. The Gardaí had met a number of people with knowledge of the Home and the burial ground including representatives of the Sisters of the Bon Secours and the two men who had found bones at the site in the 1970s. The Gardaí concluded from their analysis of maps and from inspection of the site that the burial ground was about three times larger than the area which is now maintained as a burial ground. They concluded that the back gardens of some of the properties on the Athenry Road were part of the burial ground.

It’s great to discover your site. So many are quick to believe msm. The truth will eventually see the light of day.