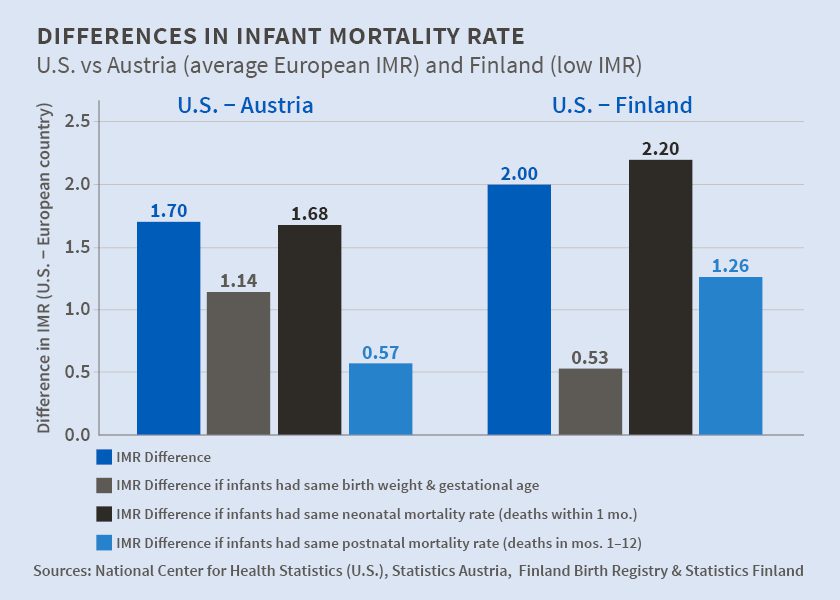

Infants in 21st century England, who are born to unmarried mothers, are 30% more likely to die than those born to married parents. The Irish think that because infant morality rates were high in mother and baby homes that children were abused and murdered. Why are the English not accusing their unmarried mothers of abuse and murder of their children through interpreting statistics the same way as the Irish? The answer is simple, a high IMR is not evidence of poor quality care.

Illegitimate infants in past times are generally considered to have been among the most vulnerable population groups: in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for example, children born out of wedlock were around twice as likely to have died before the age of one year than those born to an official union. The illegitimate penalty decreased as overall infant mortality rates fell in the twentieth century, yet today, in the early years of the twenty-first century, illegitimate infants in England and Wales are still 30 per cent more likely to die during their first year of life than legitimate infants. Even those reported to be illegitimate but registered by both parents living at the same address are 17 per cent more likely to die in infancy.

This is not a mistake, the authors reference the UK publication ‘Health Statistics Quarterly, 2004’, which I have checked and can confirm the accuracy of the statement. If this UK statistical gathering proves anything, it is that Irish social and medical research is disconcertingly deficient and the consequences are manifest through misinformed beliefs and assertions, which are nearly always expressed with oikophobic belligerence.

EJ

Ref:

Reid, Alice, Ros Davies, Eilidh Garrett, and Andrew Blaikie. ‘Vulnerability among illegitimate children in nineteenth century Scotland’. Annales de démographie historique 111, no. 1 (2006): 89–113.